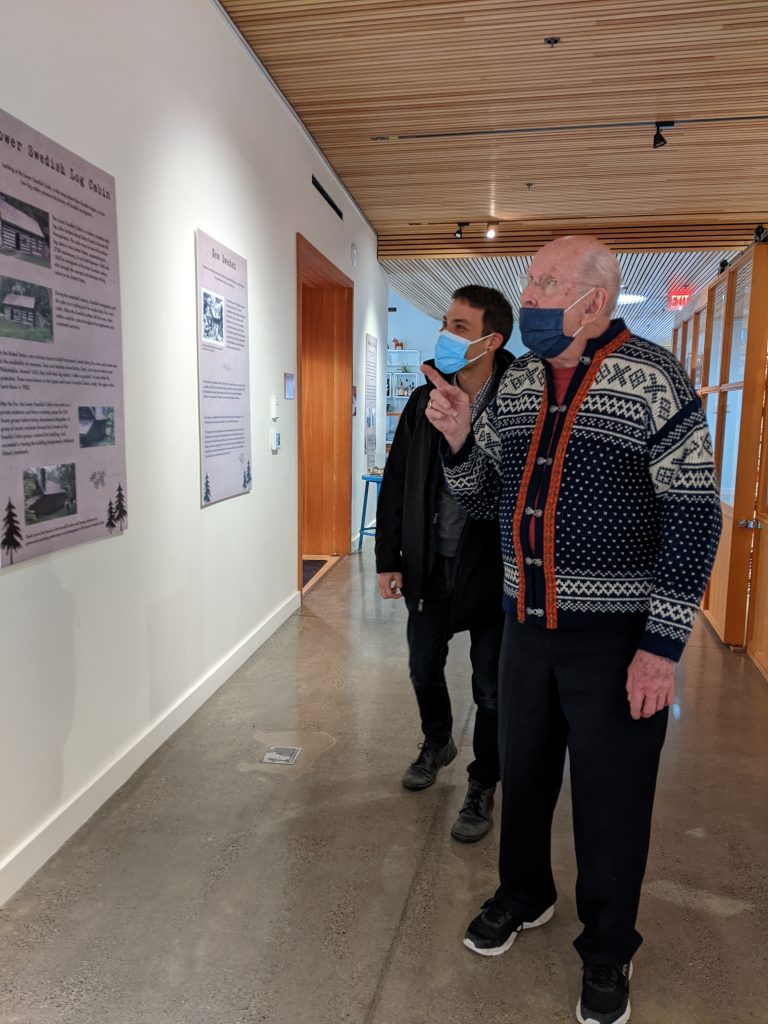

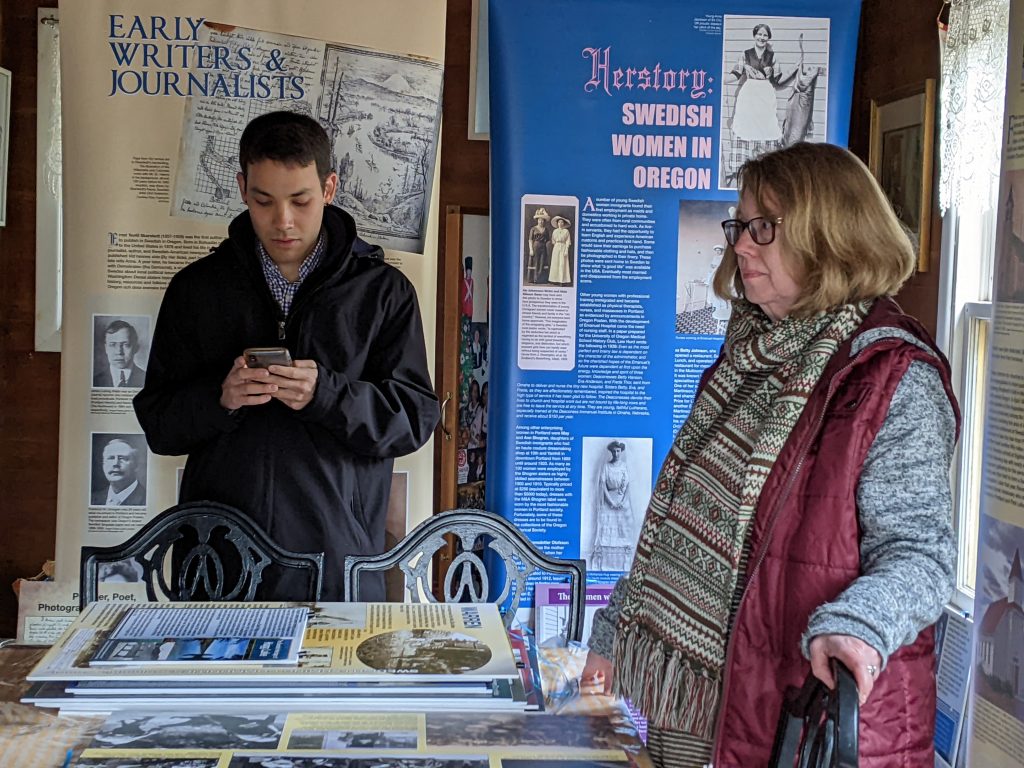

Earlier this spring in March, several SRIO board members had the pleasure of meeting with Simon Shachter, PhD candidate from the University of Chicago. Simon’s dissertation in the field of sociology centers on the 19th and early 20th century immigrant experience in major cities along the West Coast of the United States. As Swedes were among the most prominent immigrants at the time, Simon spent an afternoon perusing highlights of SRIO’s 2019 exhibit From Sweden to Oregon: The Immigrant Experience 1850-1950, and discussing Swedish Oregon’s history with board members David Anderson, Ann Baudin Stuller, Ross Fogelquist, and Rhonda Erlandson. We were as interested in Simon as he was with SRIO, especially when we learned of his own rich immigrant family history and his goals for the future. What follows is an interview between Simon and SRIO board member Rhonda Erlandson.

Tell us about yourself and your background. Where did you grow up? What activities do you enjoy outside your scholarly pursuits?

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area on the Stanford University campus, so I’ve always been surrounded by academia and an interest in research and teaching. A lot of my hobbies are closely related to my scholarly activities. My central research interest is the nonprofit sector. One of my main activities outside of academia is supporting the organization I founded called YCore. The purpose of YCore is to help young professionals get involved in supporting, advocating, and building solidarity with more marginalized members and organizations in their local community. I also enjoy doing logic puzzles, long-distance running, and baking and eating chocolate chip cookies.

You are fourth generation Japanese. When did your ancestors come to the US and where did they settle? Were there particular challenges or successes they experienced that have become part of your family history? As you were growing up, did your family have cultural traditions that were passed down by your ancestors?

All eight of my great grandparents immigrated to the U.S. in the 1910s and 1920s, four from Japan and four from Eastern Europe. My Japanese grandma’s family settled as farmers in California’s central valley as part of a Christian, cooperative colony. Although Japanese immigrants couldn’t own land in California, the colony was supported by some trusted white lawyers who saw the damaging effects of these laws. My grandfather grew up in Oakland, California and his parents owned a laundry, one of the few types of businesses Japanese immigrants could own without facing often violent racist attacks. For both of my grandparents, the hardest part of their lives was being sent back to Japan in the years before World War II and being stuck there as U.S. citizens during the war. My grandma’s family lost nearly everything when their house was firebombed, and my grandfather refused to ever talk about his experience. They were so grateful and happy when the U.S. won the war, they named one of their kids after Douglas MacArthur. Even with a showing of patriotism they were very scared of racism when they made it back to the U.S. They refused to talk to their kids in Japanese or teach them any of the language—they felt their kids needed to be as Americanized as possible to be safe. Few cultural traditions got passed down through the generations other than the importance of rice. As my grandparents got older and explicit racism against Japanese became less of a problem, they began to pass more things down and encouraged my cousins and me to learn Japanese, bonsai (my grandfather learned this from his grandfather), and how to cook Japanese food.

Regarding my European ancestry, my great grandparents came from Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. My grandmother’s family came from what was then Prussia and settled in Corpus Christi, Texas. The Great Depression was rough on the family, but my grandmother was able to make it to the University of Texas-Austin on a full scholarship. After meeting my grandfather and having three kids, she completed a PhD studying children’s folk tales in Mexico and became a professor of children’s literature where she advocated for and exposed children to multicultural stories, art, and high-quality literature. My grandfather’s family came from Romania and lived across the U.S., seeking a suitable Jewish community for them and their kids and finally settling in Philadelphia. My grandfather became a passionate labor activist. While both rejected much of the scriptural parts of Judaism, Jewish holidays, foods, and festivities were always cause for large celebratory family occasions. My step grandfather also influenced my upbringing. His parents were immigrants from Germany, and he grew up in their candy store in Philadelphia, returning to central Europe to get his medical degree after World War II. He was always committed to giving to those in need and supporting his community, a value imprinted on me and all my cousins.

Where did you go to school and university? What were your primary areas of study and what drew you to those subject areas?

I went to Stanford and majored in Computer Science with a minor in Comparative Literature, and I didn’t take a single sociology class until I started graduate school. I love solving problems and engineering systems, but when I tried to work in the technology field, I found the problems the industry was trying to solve lacked much meaning for me. Comparative literature exposed me to different cultures and art, proving to me there were no straightforward, algorithmic solutions to most of the large-scale problems society faces. In sociology, I’ve found something of a middle ground. It’s a field which appreciates the nuances and complexities of societal problems while, at its best, seeks to find solutions to some of the thorniest issues we face.

When did you begin your PhD work at UChicago? Tell us about the subject and scope of your dissertation and how you came to focus on this topic?

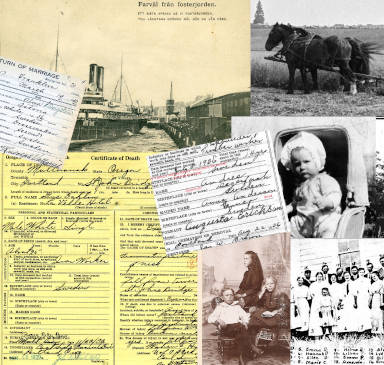

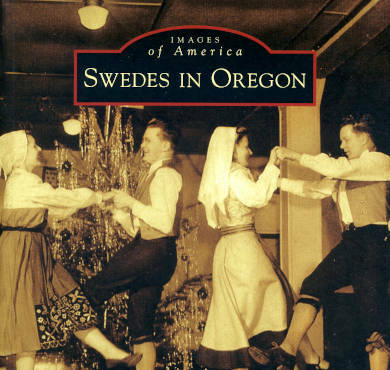

I began my PhD in the fall of 2017. My broad interest when I entered the program, and still today, is understanding the systems the U.S. uses to provide the services needed by the most marginalized people in the country. What I find endlessly fascinating are the complicated relationships between nonprofit service providers, philanthropy, government, and the people all three of those groups seek to help. It’s an incredibly convoluted and unintuitive system which does not seem to provide optimal results for anyone, especially for the people needing help. My dissertation focus began by asking how did this system get created and become the way it is today? Relatively recent research in sociology has shown these systems are unique to local areas and are surprisingly persistent across time. I decided to concentrate on the early years of cities to understand their initial creation stories, and I chose the West Coast because Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle all have widely different systems but were created around the same time facing similar political and economic forces. When I began looking into the history of these cities, a vast majority of the nonprofit charitable organizations active in politics and building relationships with government were immigrant organizations. I finally settled on my topic of understanding the role of immigrant organizations in the creation of the political institutions of West Coast cities. I’m looking at these four cities and focusing on the top three immigrant groups (by population) in each city. In Portland and Seattle, the Scandinavian communities were large and influential in terms of population and in the activity of their organizations.

How did you discover Swedish Roots in Oregon?

Most academic historic work unfortunately just focuses on what is in major university and government archives, when much of the richest material is contained within the communities themselves. I knew I had to reach out to members of each of the communities I’m studying to hear their stories firsthand and learn from them. A quick google search pointed me directly to SRIO and Nordic Northwest. David Anderson (current SRIO President) immediately responded to my email, and Nordic Northwest told me I had to talk to SRIO. I couldn’t have been happier for the connection! It’s already helped my research so much and I’m sure it will continue to do so.

In your research so far, have you observed similarities between immigrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries and those of today in terms of what made them leave their home countries and what experiences they had in the U.S.?

A consistent theme in my research is that immigrants are fighters. The predominant discourse in the news, casual conversation, and even academia, is about all the regulations and decisions and people that immigrants are at the will of. Discourse tends to focus on what affects immigrants rather than what immigrants do themselves. Just the choice to immigrate is often a wrenching one which demands incredible courage, sacrifice, and skill. Then, once in the U.S., immigrants must figure out how to survive. All do so much more than that—they also try their best to support their fellow immigrant community members and their neighbors to build a better home. I want to highlight the role of immigrants as powerful, passionate, brave actors in their own right who are intimately involved in building our society.

You mentioned that you are focusing on immigrant activities and structures in major cities along the west coast. Among those cities, which institutions are you finding to be most useful for your research?

This is a big question that I want to know the answer to as well!

The cities I am studying are Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle. These cities formed and grew to be huge cities around the same time and under similar economic, political, and demographic pressures. In general, I am interested in the political structures that encourage the formation of private organizations like immigrant organizations, and the influence these organizations have on the ensuing development of city government. The struggle I am going through now is deciding how to focus this on some specific political structures and organizations as examples. Some potential ideas right now are how do people find employment, how are deviance and crime defined and controlled, who gets control over harbor lands and interstate commerce, who is defined as a citizen deserving of voting rights and entitlements (including immigrants, women, orphans, and veterans, for instance).

What are you hoping for after you complete your dissertation?

I want to become a professor at a university where I can teach and continue to do research. I haven’t found any other jobs I love more than teaching and research, and a job that combines them and allows me freedom in what I teach and research is my dream job. I care less about where I end up geographically and more about continuing to discover how to improve our world and teach others how to do the same.

Have you spent any time in Sweden (or Scandinavia in general)? Or have you traveled to other countries outside the U.S.?

Unfortunately, I haven’t had a good opportunity to visit Sweden or elsewhere in Scandinavia. It is definitely near the top of my list of places I want to visit. I am not very well-traveled internationally since college, having most recently ventured outside the U.S. almost a decade ago. As I was growing up and while in college, I made trips to Japan, Israel, and Spain. I’m looking forward to more travel in my future.

As a retired librarian, I can’t resist asking you what you enjoy reading for fun?

I am something of an avid reader. My favorite thing to read is fiction written by women of color. Being in a white, male society so much of the time, I like to be transported to different worlds.