Introduction

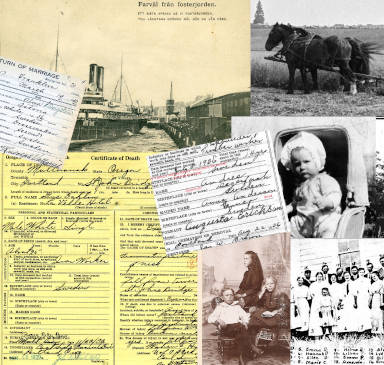

After the short-lived attempt in 1638 to establish Fort Christina and the New Sweden colony in what is now Delaware, Swedish emigration to the United States of America is usually said to have begun in earnest in the 1850s. This initial wave of new Swedish immigrants—unlike the previous government-sponsored emigrants—mostly consisted of religious groups and individuals seeking freedom from harassment from the Swedish state church, which tolerated no dissention from established Lutheran doctrine. After the American Civil War, rapidly increasing numbers of poor, landless farm workers, crofters, farmers, maids, and all kinds of tradespeople joined in the exodus. In less than a decade, the once small trickle grew into a mass emigration movement that did not end until the passing of the so-called “quota laws” restricting immigration in the 1920s and the stock market crash on Wall Street in October 1929. This seventy-five-year period prior to 1929, known in Sweden as “the Great Migration,” saw some 1.2 million Swedes—twenty percent of the entire population—leave their native country.

When migration scholars discuss immigration dynamics, they sometimes talk about “push” and “pull” factors. “Push” is a term used to represent forces that drive an individual, family, or group out of their native country. As previously mentioned, religious persecution was one such force for the early Swedish emigrants. For the emigrants who came later, poverty was undoubtedly the major push factor. But throughout the nineteenth century there were certainly other push factors for the Swedes as well, such as occasional years of crop failure and famine, a steadily growing population depressing wages, limited opportunities, class oppression (which translated into lack of social mobility), taxation, conscription, debt, legal troubles, and unhappy marriages. “Pull,” on the other hand, is used to describe an attraction emanating from the country where one wants to go. The pull factors can often—but not always—be regarded as the opposite force: The emigrant’s destination offers religious freedom, available farm land, jobs or better-paying jobs, lower taxation, social mobility, opportunities, uniting with family members already living in that country, or simply a desire for adventure. Often, any particular emigration was the result of a combination of push and pull.

In the fifteen oral histories told in this volume, two main patterns quickly emerge: We meet immigrants who are being pushed by poverty and pulled by family members already in the United States. Family in America could often sponsor the immigrant, provide money for tickets, a place to stay, and occasionally even employment. They had usually also learned English, figured out how things worked, and could help facilitate integration into American society. For some newly arrived immigrants it was a tough school. As we learn, some Swedes refused to speak Swedish with their newly arrived relatives. They were in America now, and in America you were supposed to speak English! This helps us understand why the Swedish language was often not transmitted to the next generation and how that has made keeping in touch with family in Sweden difficult for the second and third generations. Not teaching their children Swedish also gave the parents the advantage of having a secret language, something which comes up in several stories.

It is also worth noting that the emigration from Sweden to the United States in the decades after the American Civil War originated from two provinces in particular: Småland (located in southeast Sweden) and Värmland (west-central Sweden). As large numbers of farm workers, crofters, and loggers left these areas, the situation improved for the ones who stayed behind, and, as a consequence, there was less incentive to leave. Beginning in the early part of the twentieth century, the flow of emigrants increasingly came from Norrland, the northern part of Sweden. Norrland has never been heavily populated, and agricultural settlements in the vast forests inland from the Gulf of Bothnia to the treeless mountains did not start until the early 1800s. Farming in this area has always been marginal and difficult at best. As these stories make clear, emigrating from Norrland was a trend that continued well into the post-World War II period, and many of these norrlänningar [northerners] found their way to Oregon.

In several of these stories the father left for America by himself for the simple reason that there was not enough money for tickets for everyone. Some couples were lucky and were able to preserve their marriage until the men had—many years later—managed to save up enough money to send for their loved ones waiting in Sweden. In some cases the extended separation proved too difficult and eventually led to divorce, and branches of families ended up losing track of each other. Some Swedes speak of their emigration as exciting and worrisome at same time. In more ways than one, the New World was full of new sights. For example, even as late as the 1940s, many Swedes had never seen a black person except in photographs, and encountering one for the first time made an indelible impression.

Due to a lack of professional and language skills, many newly arrived immigrants could only get hard manual labor jobs that paid poorly. Many moved from place to place in an attempt to get established. Emigration also caused other kinds of hardships. Some people mentioned in these stories came during the 1920s and were caught by the Great Depression before they had a chance to establish themselves. As a result, many ended up returning to Sweden throughout the 1930s. Others stayed in America but were never able to realize their dream of financial success. Occasionally, the immigrant’s feelings of failure, while relatives back in Sweden imagined these Swedish-American emigrants to be fabulously wealthy, seem to have strained family ties.

Speaking little or no English upon arrival was a near-universal experience. Some learned English quickly, but others never felt quite at home with the new language and were most comfortable when they could speak Swedish with family and countrymen. For many of the Swedish-Americans born to Swedish or Scandinavian parents, the reverse was true. Their parents spoke Swedish and/or Norwegian, but most of them decided to not teach their children, who were often disappointed by that. Being an immigrant was something that many Swedes apparently tried to hide, and many wanted to assimilate quickly. Their children were teased in school for being immigrants, and if the parents had Swedish friends visiting, the children were asked not to bring their American friends home to play that day. They felt comfortable being Swedish in the privacy of one’s home, but not in public.

It is also interesting to note how important Swedish food was to both immigrant and second-generation Swedes in maintaining a connection to their ethnic identity. Drinking coffee, for example, has been a popular part of Swedish culture for a long time, and it was a custom that the immigrants brought with them. Whether one needed a short break from work or a visitor stopped by, it was a good excuse to “cook some coffee.” We also repeatedly hear about other traditional foods such as pancakes, meatballs, crisp bread, pickled herring, lutfisk, fermented Baltic herring, saffron buns, and cardamom rolls. Associating the smells and flavors of certain food with traditional holidays and events is not only something that ties Swedes and Swedish-Americans together, but also makes them distinct from other Americans.

Being active in Swedish organizations and lodges that work to preserve Swedish culture and heritage has also remained very important to many immigrants. Christmas and the traditional summer solstice celebration known as Midsummer stand out as the two most important Swedish holidays celebrated in the United States, but Lucia celebrations in December and more recent crayfish eating parties in August are also well attended. Immigrants and second- and third- generation Swedish-Americans alike go on trips to Sweden, but the immigrants travel back far more frequently.

Even though the individual voice—the unique story of each person—is at the heart of every oral history collected in this volume, the sum of these fifteen narratives also paints a portrait of the world outside the personal sphere. The “history” in these stories portrays a large and vibrant Swedish community where many obviously knew each other. The stories also evoke a Swedish-American world with its own restaurants, lodges, churches, choruses, dances, soccer team, gatherings, and activities that have now all but disappeared. The major turning point seems to have come after World War II, after which immigration declined and most organizations shrank in size.

Another remarkable fact that emerges from these oral histories is how resilient family ties are. Assisted by written family histories and recollections, online genealogical research, and internet communication, as well as trips back and forth across the Atlantic to meet with relatives, these ongoing activities connect families and help define what it means to be Swedish in America today. In several of these stories, we discover that family members on both sides of the Atlantic still keep in touch with each other over a hundred years after the first emigrant left Sweden!

Finally, a few comments about the challenging nature of editing oral histories might be in order. Few people speak the way we expect to read written language, and almost all transcribed narratives are challenging to read “as is.” Spoken language is full of things we rarely see in print: repetitions, mistakes and corrections, unfinished sentences, and all kinds of fragments. Sudden associations sometimes lead the narrative astray. Pronouns can occasionally appear ambiguous or plain wrong. Most narratives also meander freely and rarely follow events chronologically, and must therefore be rearranged for coherence and flow.

Whenever a person tells a story, there is also always a great deal going on beyond the words themselves. For example, the narrator may show or point to an object—a picture or a treasured heirloom—to illustrate something important, and this should ideally be conveyed in the narrative somehow. There are also facial expressions, gestures, and all sorts of emotional qualities embedded in the way words are being spoken. Qualities like laughter, seriousness, irony, or sadness are sometimes recorded by the tape recorder, but they can be difficult to convey in print. If one tries to indicate them in brackets or parenthesis, the text quickly reads like a playwright’s directions to the actors. A conscious decision has been made to not take the text in that direction, but to move the narratives a step closer to written language. An occasional exclamation point or italicized word has been left to indicate an emphasis of some sort. Occasionally a footnote has been inserted to explain or add something which might not be generally known.

It has been a privilege to work with these stories and a great pleasure to get to know all the narrators, listen to their experiences, feelings, and thoughts. I hope you will enjoy their stories as much as I have.

Lars Nordström

Beavercreek, Oregon, August 2013

Excerpt from

Swedish Roots, Oregon Lives

Oscar Nastrom (1898 – 1987)

I have followed music most of my days. I started playing when I was still quite young. My father was a music teacher, and he had a chorus, but I never sang under him. I was too young. I enjoyed singing, though. I played in the orchestra there and played dances and different instruments, saxophone and clarinet and so on. That’s how I got started with music, from home.

When I left Sweden in 1923, there were about a hundred people at the station to wish me luck. My mother went with me; she wanted to see me off. She was a great mother. As she was about to return back home—it was about a day’s trip—she said: “You come back in five years!” I had promised her I was going to come back in five years. I left her and went to Stockholm and from there to Norway, because at that time you didn’t fly. There were boats in Stavanger fjord, big nice cruisers. I don’t know if one of the boats was American. Then I went to get my ticket. They didn’t have fourth class, so I had to buy third class. When I came to board they had to examine me to see that I didn’t have any fleas. This was because of the third class ticket. I don’t know if they did that to the passengers in second class. They had me stripped down there, a bouquet in one hand, my suitcase in the other, and my pants down. That’s how I left Norway. I have told this story many times. In fact, one guy painted a picture of it.

I had quite a trip to America. You see, there was my fiddle. I played it on the boat from nine to ten thirty, and then we took up a collection. There was also an accordion player from the south of Sweden and they gave us money, so boy, I had money when I got to New York. When I left I had forty-seven cents; when I came to New York I had fifty dollars, think of that! We had a wonderful time. In Sweden we lived on the Gulf of Bothnia coast, and sailors came from all over the world, and we boys mixed with them. They spoke French, Italian, English, German, and we spoke with them somehow, so I didn’t have any trouble with English when I got to New York.

When we got to New York, we had to go through Ellis Island. You had to get stamped and marked, and I got along alright. I was looking around and could see a Swedish flag way in the back somewhere. I went in there and they were talking Swedish so I didn’t have any trouble. I got done and kept going. I had to show my fifty dollars. There were two other fellows there from the same boat and the same place in Sweden, and all three of us used the same fifty dollars going through. It was passed from one to the next, and then I got it back. They were going to Detroit to find some work there. We had grown up together and decided to go at the same time. Yes, that’s how the trip went, and I landed in Omaha, Nebraska.

I came really early in the morning, and there was nobody at the station. My brother was supposed to be there but wasn’t. My sister lived there, too, but she wasn’t at the station either. So I went into the building. A man was sitting there at the telegraph, and I asked him if there was a taxi I could get. He asked me who I was, and it turned out he had been told that I was going to arrive, so he said to just wait and take it easy. So I sat there, and a guy drove up along the depot, and I asked him if he was a taxi. “Yep,” he said, but he wasn’t a taxi but the foreman at the company where my brother-in-law worked. He had been told to pick me up. We didn’t talk too much. He stopped at a place, and I asked if we were at my sister’s. But he just let me out and left. An old fellow came up and said, “Hello, Oscar!”

“Hello…,” I answered. I didn’t know where I was, and asked for Frida. The old man didn’t answer me right away. He was talking about the weather, how hot it was and pointed toward the sky, and I thought that maybe she had gone there. Anyway, then a girl came down a second staircase, and I had seen her in pictures before. I knew who she was and then I knew where I was—at my sister’s husband’s father’s house. The old man was the father of my sister’s husband. So that was OK. He put my suitcase on his back, and we took off. We had to walk six or eight blocks before we came to the right place.

My brother had two young daughters, who said they were so surprised that “I wasn’t talking Swedish, but spoke English all the time.” My brother asked me when I wanted to start working, and I told him I would start right away. My brother had a truck, a nice ice truck, but I didn’t work with him. I started working with an old fellow who used a team of horses to haul ice. We bought ice from some people down there who made ice. Then the old man quit, and the foreman asked me to take the horses and keep up the route, so I did. Just think of that! Those horses knew where to go. They had been at it for ten or fifteen years, so I didn’t have any trouble. They stopped, and people had signs on their doors telling me how much ice they wanted. I worked there for some time, and I enjoyed it very much.