The Story of an Immigrant Newspaper

Introduction

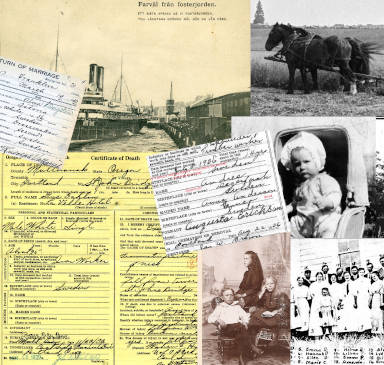

In this fascinating study of Oregon’s major Swedish-language newspaper, Oregon Posten (1908 – 1936), Victoria Owenius explores the multifaceted role of an immigrant newspaper within American society during the first half of the twentieth century. Before 1908, Oregon remained completely isolated from Sweden. The 19th century immigrants had literally traveled to the other side of the earth, and found themselves cut off from family, friends and homeland. The Oregon newspapers provided no news from the old country, and even if they had, many immigrants would not have been able to read them since they did not know much English. There were a few major Swedish-American newspapers in the East and Midwest, but beyond that, people had to write letters.

Fairly large numbers of Swedes had come to Oregon after the arrival of the railroad in 1883, and by the early nineteen hundreds there was a fairly substantial Swedish population in the state. Therefore it is not surprising that Oregon Posten became an instant success among the news-hungry Swedes when it started publishing in 1908.

Oregon Posten quickly created a wide, international community of readers. The paper provided a steady flow of national and local news from Sweden that the immigrants craved. It also provided important news about the United States and Oregon in Swedish, helping the immigrants learn about their new environment in their native language. Because the paper wrote about Oregon, it also attracted outsiders curious about the state. These included Swedes in other parts of America or Canada who were contemplating the possibility of moving there, as well as people in Sweden who had relatives and friends living in Oregon and who wanted to stay informed.

In addition, Oregon Posten became a tireless promoter of the state and its Swedish communities, encouraging other Swedes to join them. It emphasized Oregon’s rich natural resources and moderate climate, while simultaneously building a strong, cohesive community feeling. The paper ran stories about the Swedish settlements scattered across the state, and always provided space for such things as congregations and church services, the various events sponsored by Swedish organizations, wedding notices and obituaries. In addition, the paper always contained a great variety of ads for Swedish businesses and services in the Portland area. In short, the newspaper quickly connected the Swedes of Oregon into a statewide network.

Finally, Oregon Posten also played an important role in the preservation of language, heritage, culture and identity. In a time when Swedish books were hard to come by, the newspaper became an inexpensive and highly appreciated source of entertainment and culture by printing jokes, poems, stories and serialized novels. It always supported the teaching of Swedish to second generation Swedish-Americans, and it was in favor of maintaining Swedish customs and traditions. And when a powerful wave of anti-immigrant sentiment swept the United States during the turbulent years of World War I, requiring demonstrations of patriotism, the paper rallied behind the Swedish-Americans. Oregon Posten always argued that it was possible to be both a patriotic naturalized American citizen, and someone who simultaneously and proudly preserved his or her native language, culture and identity.

Lars Nordström, Ph.D.

The Rise of a Swedish-American Paper

Jag ville skrifva en liten sång

Att vår goda tidning Posten prisa.

Förutom den så vore tiden lång,

Min längtan kan det bevisa!

Mot hvarje onsdag jag hoppfullt skådar,

Ty Postens ankomst för mig den bådar.

Det finnas nyheter af hvarje sort

Från alla delar utaf verlden,

Och skulle ödet dig vinka bort,

Tag Posten med uppå färden.

Då kan din tid du angenämt fördrifva

Och ”långsam” hinner du ej blifva.

I want to write a little song

To praise our good paper the Post.

Without it time would be so long,

My longing can prove that!

I eagerly look forward to every Wednesday,

Then I know the Post is on its way.

It is filled with news of every kind

From all parts of the world,

And if fate would take you away,

Bring the Post along on the journey.

Then you can pleasantly pass away the time

And you will not have time to be bored.[i]

This poem was written during Oregon Posten’s first year of publication by a dedicated subscriber named Emma, and it reveals her appreciation for the paper. Oregon Posten consisted of different sections that offered both news and entertainment in the form of novels, humor, and poems. The paper may not have seemed like much compared to American dailies, but for many immigrants this was the only connection they had to Sweden. Despite the obvious need for this publication, a Swedish newspaper had not always been successful in Oregon. Six different Swedish papers and journals had been launched in Oregon before Oregon Posten, and all had failed.

The first Swede who attempted to create a newspaper in Portland was the famous Swedish-American journalist and editor Ernst Skarstedt. In 1890 Skarstedt published a couple of issues of a campaign newspaper called Demokraten [the democrat]. The purpose of this paper was to educate people about the political situation in Oregon. Following this came a weekly in 1892 called Folkets Röst [the people’s voice]. It only lasted three issues. J.L. Wallin published Portland’s Veckoblad [Portland’s weekly paper] in 1894. This paper survived almost a year, despite the relatively small group of Portland Swedes. After the failure of Portland’s Veckoblad there was no Swedish newspaper in Portland until 1906 when J.L. Wallin returned with an illustrated monthly titled Nordvestern [the northwest]. However, this magazine quickly failed too.[ii] These failures were more than likely due to the lack of readership.

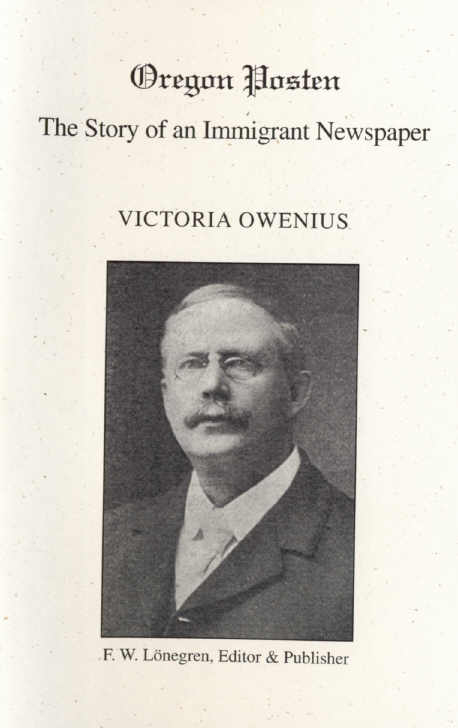

In the spring of 1908, J. Hyllengran from Seattle arrived in Portland and started a paper called Svenska Oregon Posten [the Swedish Oregon post]. This paper published six issues and many people were disappointed when it ceased to circulate. At this time Reverend J. Ovall published a church paper called Härolden [the herald], but this paper failed too. But in October 1908, Fredrik Wilhelm Lönegren arrived in Portland from Seattle to start the Swedish newspaper that was to take root and survive until 1936.

Fredrik W. Lönegren was born in Wederlöf’s parish in Kronobergs County, Sweden, in 1860. His father was a minister and his mother also came from a family of clergy. He was educated at two Swedish universities and worked as a teacher in Jönköping until 1889, when he decided to leave for America. He went to St. Paul, Minnesota, where two of his older brothers were living.[iii] Shortly afterwards he moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he worked as a teacher. Lönegren was married to Catherine L. Wedmark. She was a teacher from Wisconsin and the daughter of Swedish immigrants. They had one daughter, Irma born in 1893.[iv] Both Lönegren and his wife were members of the Swedish Historical Society of America. From June 1891 to February 1896 he served as the editor of the Swedish paper Duluth-Posten in Minnesota. From 1897 to 1901, he was the branch department editor and manager of Svensk-Amerikanska Posten [the Swedish-American post] in Duluth. In 1897 he became a member of the library board in Duluth, and encouraged library purchases of Swedish history and literature.

Lönegren was very active in politics. In Minnesota he was a delegate to several state conventions and a number of other political meetings. He gave more than one hundred political speeches within the state during John Lind’s gubernatorial campaigns in 1894, 1896, 1898, and 1900.[v] Lönegren was also the president of the Scandinavian Lind Club in Duluth for many years. John Lind was a Democrat and so must Lönegren have been. This is interesting considering that the majority of the Swedish newspapers (and Swedish-Americans) were Republican.

In 1902-1904 Lönegren worked in the real estate business in Little Falls, Minnesota.[vi] After that he worked for several different newspapers including Svensk-Amerikanska Posten in Minneapolis, Nordvesterns Handelstidning [the Northwest’s trade paper] in Duluth, and The Pacific Tribune in Seattle. [vii] In Seattle Lönegren also worked in the real estate business. In addition, he assisted Ernst Skarstedt with his book Washington och Dess Svenska Befolkning [Washington and its Swedish population], a promotional book encouraging Swedes to move to Washington.[viii] When the book came out in 1908 his intentions were to promote Swedish settlements and sell irrigated land, while working with publishing on the side.[ix]

But instead, Lönegren moved to Oregon. He knew that starting a paper would not be easy; therefore he was happily surprised when he found receptive Swedes in the area. Within one month of arriving in Portland Lönegren managed to collect enough Swedish stockholders to start a publishing company, The Swedish Publishing & Printing Co. Initially, the company began with thirty stockholders; eighteen months later it had increased to almost forty. The paper was so successful that one year after its creation the stockholders received a 10% dividend. The first issue of Oregon Posten was published December 2, 1908. F.W. Lönegren became the editor of the newspaper, and five years later he also became its publisher. He received great help from his wife who took care of a large portion of the office work. Ernst Skarstedt described Lönegren as having a “free and easy style.” Skarstedt also wrote that Lönegren’s diverse experiences and his incredible capacity for work and persistence may explain why he succeeded where others had failed.[x] The paper’s travel agent became Mr. Andrew Peterson, and C.M. Newman ran the printing press. The paper published weekly until the final issue on January 23, 1936.[xi]

The successful start of Oregon Posten had much to do with the fact that the Swedish population of Oregon was then at its highest levels. By 1910, 10,099 foreign-born Swedes lived in Oregon compared to 4,555 in 1900.[xii] There was an obvious correlation between the number of Swedish-born people in America and the number of Swedish-American newspapers. The peak number of Swedish papers in America and the year with the largest number of Swedes in America both occurred in 1910.[xiii] Compared to his predecessors, Lönegren had a larger foundation to build a successful newspaper upon. The content of the paper also seemed to be a style that was appreciated by Swedes because it appeared throughout the nation.

In 1909 the price of a US subscription was $1 per year and 65 cents for six months. If you lived in Canada the price was $1.50 and in Sweden $2.00. There were many people who subscribed to Oregon Posten for their relatives back in Sweden. Each issue of the newspaper was often read by many, so that the number of subscribers did not necessarily portray the total number of readers. This was a financial challenge for a small newspaper. The paper’s peak readership came in 1912 when 3,250 people subscribed to Oregon Posten. In 1915 the paper had 2,800 subscribers, a number that remained unchanged until 1921.[xiv] The fact that Oregon Posten did not lose subscribers during World War I was remarkable, considering that numerous immigrant papers lost readers during that time, especially the German-American press. Ten Swedish weeklies in the United States disappeared from the market between 1915 and 1920, the main reason being the doubling of the printing costs.[xv] Lönegren also suffered from these cost increases, but managed to survive the war years by increasing the subscription price and urging his readers to renew their subscriptions. Oregon Posten also experienced less competition than papers in other parts of the country.

One of the gimmicks Oregon Posten used to win subscribers in 1909 was to offer a fine pair of scissors with the purchase of a subscription. This tactic worked, because many letters received by the paper thanked them for – or inquired about – the scissors. In 1916 anyone who ordered a one-year subscription for their family in Sweden also received a copy of the 1915 special issue about the Swedish community.

The format of the newspaper basically stayed the same throughout its 28-year life span. The first issues of Oregon Posten had six columns and eight pages. Half a year later the newspaper expanded its format to seven columns and eight pages. Every issue of Oregon Posten contained several recurring sections. This included American and Swedish news. Many of the Swedish news stories came from the Swedish-American News Bureau in Stockholm. In addition, a whole page was dedicated to news from each province in Sweden. The opportunity to read news from one’s home region warmed many a lonely immigrant heart. For an outsider provincial news might seem trivial, but according to a study of the Swedish-American press[xvi] the Swedish news section was the most popular.

——————————————————————————–

[i] Oregon Posten, 28 July 1909. All translations by the author unless otherwise indicated.

[ii] Oregon Posten, 1 June 1910.

[iii] Ernst Skarstedt, Washington och dess Svenska Befolkning [Washington and its Swedish Population] (Seattle, Washington: Washington Printing Co., 1908), 440.

[iv] Ernst Skarstedt, Oregon och dess Svenska Befolkning [Oregon and its Swedish Population] (Seattle, WA: Washington Printing Co., 1911), 142-143.

[v] Skarstedt, Washington, 440-441.

[vi] Ernst Skarstedt, Svensk-Amerikanska Folket i Helg och Söcken [The Swedish-American People in High Days and Working Days Alike] (Stockholm: Björck&Börjesson, 1917), 174.

[vii] Skarstedt, Oregon, 142-143.

[viii] This was the first of a trilogy of similar books Skarstedt assembled on the Pacific states.

[ix] Skarstedt, Washington, 440-441.

[x] Skarstedt, Svensk-Amerikanska Folket, 174.

[xi] Skarstedt, Oregon, 120.

[xii] Smith, 34.

[xiii] Ulf Jonas Björk, “The Swedish-American Press: Three Newspapers and Their Communities” (Ph.D. diss., University of Washington, 1987), 36.

[xiv] Finis H. Capps, From Isolationism to Involvement; the Swedish Immigrant Press in America,

1914-1945 (Chicago: Swedish Pioneer Historical Society, 1966), 234; Smith 55.

[xv] Björk, Swedish-American Press, 37.

[xvi] Schersten, 55.