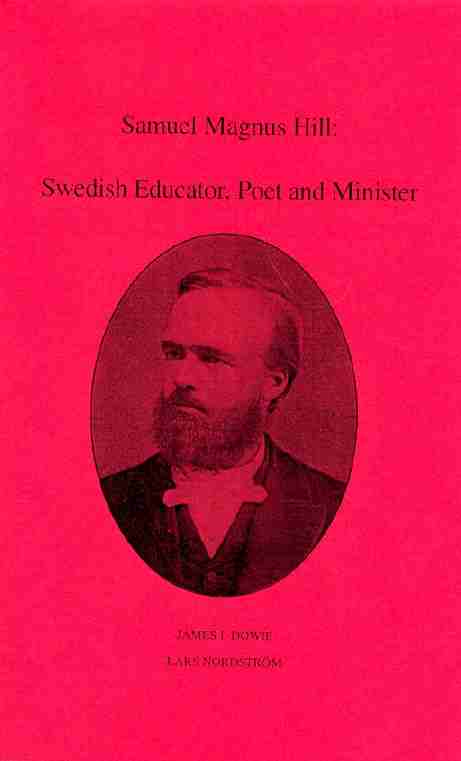

This biographical portrait of Samuel Magnus Hill, written by James Iverne Dowie and originally included as two separate chapters in his doctoral thesis (later published as Prairie Grass Dividing in 1959), describes Hill’s life from his arrival in the United States in 1868 to his move to Oregon in 1915

Introduction to Samuel Magnus Hill

This biographical portrait of Samuel Magnus Hill, written by James Iverne Dowie and originally included as two separate chapters in his doctoral thesis (later published as Prairie Grass Dividing in 1959), describes Hill’s life from his arrival in the United States in 1868 to his move to Oregon in 1915. Dowie, writing more than thirty years after Hill’s death, never had a chance to interview Samuel Magnus Hill, but based his research on some of Hill’s personal papers saved by his daughter, Cordelia Hill Barnes, on interviews with people who knew him, and on material extracted from various archives. Sadly, some of the papers studied by Dowie, such as Hill’s unpublished memoir, now appear to have been lost. On the other hand, among the Hill documents that fortunately have been preserved in the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana College (where Hill was a student in the late 1870’s), there is material that Dowie never knew existed (and therefore never wrote about). The archive contains, for example, a copy of a Hill typescript entitled Sverigeresan [the trip to Sweden], describing a journey back to his native country in 1901. For these reasons it is important to keep in mind that Dowie’s study is, on the whole, an attempt to describe the push toward higher education among the Swedes in Nebraska, and not a complete biography of Hill’s life. A biography Hill’s life still needs to be written.

Following Hill’s university education, his years as a college instructor at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota, and his stint as an unsuccessful Lutheran missionary among Scandinavian Mormons in Utah, Hill was called by a newly founded Swedish school called Luther Academy (later renamed Luther College) in Wahoo, Nebraska. Serving initially as a teacher, but eventually also as the school’s president for fifteen years, Luther College became Hill’s mission in life and the main focus of Dowie’s study. But Hill had yet one more incarnation in a very rich and varied life—that as minister and poet in a small Swedish community in Oregon. A brief synopsis of those years has been added as a postscript.

Lars Nordström, Ph.D.

Excerpt of Samuel Magnus Hill

THE FINAL YEARS IN OREGON, 1915 – 1921

In 1915, after having served the community of Swedes in Nebraska for more than 30 years, Samuel Magnus Hill relocated to Oregon. James I. Dowie hints in his study that Hill’s move out west was not completely voluntary and that there had been a conflict of some sort. This is confirmed by a couple of lines in a poem entitled “Ett tackrim” [a rhymed thank you], composed by Hill a few years later. In the poem he writes: “I perceived a threat, that there was a desire to drive / me away without mercy. // A mistake surely, that’s what I hope.” Obviously something had happened, even though no additional details are to be found in the poem.

Dowie suggests that Hill’s sabbatical was related to the stormy emotions sweeping the United States during the initial years of World War I, and that it was based on perceptions that Hill was pro-German. There is ample evidence supporting the claim that Hill was pro-German. We know, for example, that Hill’s mother, before marrying Hill’s father, had worked as a maid in Germany and was quite versed in the German language, making Germany part of his family history. Furthermore, among Hill’s papers there are several long poems consisting of thumbnail sketches of various countries, and Hill lauded “Germania” in an undated piece (written in English) in the following way:

Deutchland, the home of the free, that never would bow to the Roman,

Varre returned all alone, when met by the intrepid Herman.

Rome could not shackle thy sons, not even pretending religion.

Luther, the hero at Worms, appealed to the court that is highest.

Statesmen, and sages and poets and singers and writers and artists

Come from thy soil to ennoble the world, thou land of the Teuton.

That Germany was the birthplace of Martin Luther, the man who, in Hill’s view, had saved Christianity and brought the world the only true light, certainly also gave it special importance. (Having been a Lutheran missionary in the mid 1880’s, Hill obviously felt very strongly about this.) And in addition to being a “Christian socialist,” as Dowie calls him, Hill remained a fierce anti-imperialist to the end of his life, and the empire he railed against was the United Kingdom (especially the opium trade in China and the treatment of India). As an example of this one can quote a couple of stanzas from the satirical “Engländarehelgonen” [the English saints], in which the poet finds the British anything but saintly in their dealings with India:

How Christian it is to use machine guns

against peaceful women and children,

to kill the hope of independence that existed

among shepherds and shy shepherdesses.

. . .

It is you that are the enemies of world peace

to a much greater degree than most.

One can not find world peace and freedom

in a mighty pirate’s nest.

And finally and perhaps most importantly, Hill was also, as his book of satirical poems clearly show, a vociferous pacifist. Hill always took a strong, anti-militaristic stance and did not think that World War I concerned the United States. How serious the rift really was between Hill and the Wahoo community (and the Board of Luther College) is impossible to say today. Perhaps other issues had been involved as well. Still, the fact remains that Hill left on a sabbatical to distant Oregon in 1915, and that the year there turned into a permanent move. Hill never returned to teach at Luther College again.

Hill’s sabbatical year in Colton was not, however, a typical retirement since he had simultaneously agreed to fill in temporarily as minister of the Swedish congregation, a position that had recently become vacant. (Substituting as a minister was something that Hill had done in Nebraska too.) Hill’s move to Oregon was not serendipitous, but had to do with the fact that several of his former Swedish students and their families had relocated there. The large Hult family was among them, and they had been instrumental in coming to Colton to get the newly organized Swedish colony going. Other Nebraska Swedes had followed, so in a sense one can say that Hill followed friends and countrymen out west. The Swedish community in Colton was referred to as Carlsborg, and it was another dream of the indefatigable Swedish-born minister C. J. Renhard, who had also been instrumental both in building the new, large Immanuel Lutheran church as well as founding the Swedish Emmanuel hospital in Portland. Carlsborg was Renhard’s dream of creating a small self-contained Swedish Lutheran community within the United States, a place where Swedes could live among other Swedes. Colton was located in the foothills of the Cascades, about 30 miles southeast of Portland, and it had a regular share-taxi service that made it easy to visit the city.

Hill immediately seems to have taken a liking to Oregon’s mild climate and green forests, and later that first fall he published an enthusiastic article promoting Carlsborg: “A more suitable place could hardly have been chosen for a Swedish community than the beautiful Milk Creek Valley with its fertile land, excellent climate, and romantic location. … [Renhard] was convinced that a great service could be done to our Swedish people by honestly guiding those who were looking for land on which they could settle; that Swedes in general succeed best in this country as farmers; that Swedes like it best where other Swedes live, and that the work of the church is much easier in a small community.” The article goes on to tell the brief but successful history of the Swedish settlement, the main families involved in the enterprise, and concludes by saying that “those who move here feel content and happy and they recommend the area to their relatives and friends.” In short, Hill was adapting quickly to what was to become his new home.

Hill’s sabbatical in Oregon also gave him more time to write, and judging from the surviving number of poems dated from this period, his literary output increased significantly. He was also busy trying to find a publisher for his recently completed translation (into English hexameter) of Virgil’s Æneid, something with which he was never successful. During his first year in Oregon, Hill had put together a collection of poems entitled Uggletoner i Vargatider [Laments in the time of the wolf]. The book was published in Portland, Oregon (at the poet’s own expense), and the first ad appeared in Oregon Posten on August 30, 1916. It was a chapbook in forest green wrappers with eight black owls in a row above the title. The price was 25 cents and it could be ordered directly from the author in Colton. Even though it contained poems on a number of different themes, it was mainly a book that argued ironically and satirically against the senseless death and destruction of World War I.

Hill was a frugal man and often recycled incoming correspondence into writing paper by simply composing new things on the back, and thanks to this habit we can catch a few glimpses of his anti-war activities. One of his Colton sermon texts is written on the back of a letter from the current United States Senator from Oregon, Harry Lane. The senator writes: “Like yourself, I do not believe in the exporting of munitions of war to any of the nations of Europe at this time, or any other time when they are engaged in bloody strife.” Obviously, Hill was on a peace offensive to his elected representatives, trying to keep the United States out of World War I.

It was also a time when Hill seems to have worried about health and money. In a letter to his friend N.G. Swan in the fall of 1916 he writes about a sick daughter, and is concerned about running out of energy and not having enough money saved for his retirement. (Hill laments the low wages earned by teachers everywhere, and the impossibility of saving anything.) Still he concludes: “But I have no reason to complain. They [Luther College] gave me a one-year sabbatical with full pay, and that is more than any other school.”

The same fall, officially ending his sabbatical year, Hill decided that if the Carlsborg congregation wanted him, and the required credentials could be obtained to serve as their permanent minister, he would resign from Luther College and seek an ordination. According to Carl J. Renhard, the wish to keep Hill was unanimous and he received many recommendations. In 1917, at the Nebraska Conference, the Augustana Synod ordained Hill (bypassing its normal requirements of seminary training and customary examination by the Augustana Board of Ministers). Hill now had, at the age of 66, entered what he called “his real mission in life,” claiming that “everything else had merely been preparation.”

Hill officially took on his ministerial duties in this small Swedish community, writing his sermons and participating in community life. Even though he often wrote about abstract things such as Christian dogma, or against social injustice, the madness of war and social Darwinism, he also frequently employed his services as a poet in the daily events of the community. These “occasional” poems describe more mundane events such as the birthdays of neighbors, rhymed thank-you notes, anniversaries and celebrations of the new year. Music had always been an important part of Hill’s life (he taught music both at Gustavus Adolphus and Luther College, and he often played in churches), and throughout his life he wrote many songs. One of the songs composed at this time is called “The Oregon Song,” once again revealing his attempt to forge a new sense of place in the West. In another interesting piece entitled “I den täcka Karlborgsdalen” [in the pretty Carlsborg Valley], he celebrates the beauty of his new home to the well-known melody of the 18th century Swedish poet Carl Michael Bellman. A poetic snap-shot from 1916 provides us with a glimpse of Colton early one Christmas morning, and it reveals that Hill could be a perceptive observer of his surroundings:

Lights flicker along the forest’s edge,

the sound of creeks are heard all around,

gentle breezes sway the trees,

stars glitter in the deep blue sky.

Lanterns approach from all around,

sparkling diamonds cover the ground.

The Karlborg Valley is filled with light,

people gather in the house of the Lord.

Perhaps Hill would have written an entirely different kind of poetry had the times been different. His poem “Mundus vult decipi,” apparently addressed to a particular individual, contains a brief, letter-like postscript: “We are doing well here and enjoy the rain and sunshine in the beautiful forest. But no nature poems come to me. It is the practical things, the increasing adversity and poverty, the ignorance and the law of the predator that gets my harp going, no, it puts a trumpet to my mouth that calls to attention.”

Hill’s ordination in the spring of 1917 coincided with the United States declaring war on Germany. This must have been a great personal disappointment to Hill, and the new situation made things complicated for his regular newspaper pieces, which he had been accustomed to writing uncensored for more than twenty years. The US government, suddenly worried about spying, public opinion, allegiances and media control, now required all foreign language newspapers published in the US, to translate anything that had to do with the war. Hill could still write what he wanted, but the chances were that anything that went against official policy would never be published. This state of affairs did not improve; on the contrary, it got worse. Early in February 1918, Hill’s new career choice as pastor of a congregation, what he had called “his real mission in life,” apparently boomeranged on him. He now received a letter from a newly formed government entity within Clackamas County (in which Colton was located), ordering him to join in the war effort by helping to raise $750,000. The letter opens: “Dear Worker: Our country is at war. This means that we, to win it, must be a united people, each discharging his daily personal responsibilities.” “Rev. Hill” was now appointed head of one of three departments, and was bluntly told that: “You are to co-operate … and appoint your local helpers. …The heads of these departments will attend these meetings …” And the letter ends: “DO NOT FAIL US.” It is not surprising that Hill turned this letter over and composed a poem with a title like “Down in the Deep, Blue Sea” on the back of it. His new position must have seemed a great irony since it ordered him to lead and serve a war he had fought so long and hard against. As a result, some of Hill’s poems now reveal a tiredness and a withdrawing from the world that had not been there before: “Let the madmen make their noise, …/ let them keep at it, let them go on / reasoning with them is futile.”

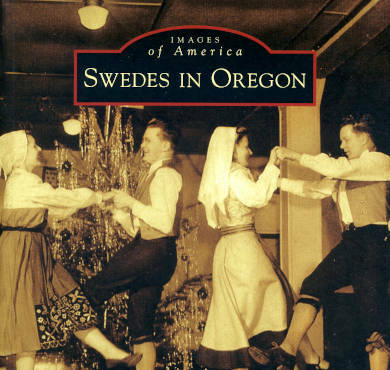

It is estimated that some 10 – 15,000 Swedes spread out across Oregon between statehood in 1859 and World War I, and wherever there were sufficient numbers to support them, Swedish congregations were formed. Towards the end of—and after—the war, Hill took occasional trips around Oregon and the Pacific Northwest to visit such Swedish congregations, delivering sermons, meeting fellow Swedes, or attending various church-related events. Many of Hill’s Oregon poems have short notes added to them, indicating their original place of composition, and they show, for example, Hill visiting Tacoma, Washington in the fall of 1917, and Gooseberry in Morrow County in eastern Oregon in the spring of 1918. Other poems refer to places and events in the titles themselves, and Hill is present “At the Tenth Anniversary of Elgarose, Oct.9, 1919,” a small community located about five miles east of Roseburg. Another poem places him at “The Forty-Year Celebration in Astoria on March 23. 1920,” A church program in the Hill archive also show that Hill visited Marshfield (which in 1944 changed its name to Coos Bay), a city along the coast which had a fairly large Swedish population.

Still, in spite of his travels, Hill seems to have lost some of his energy. On his 69th birthday (January 10, 1920) he writes a poem in which he says: “Alas, happy he who could swing himself to heaven, / and not have to remain here on earth.” Later that year, on June 5, while again visiting the Swedish congregation in Elgarose, Hill suffered a mild stroke. He was able to deliver his Sunday sermon and to travel back to Colton by himself on Monday. However, his ability to speak quickly became much reduced, as was the use of his right side, and he soon became completely incapacitated. C. J. Renhard reports that Hill “did not suffer very much, [and that he] was fully conscious, calm and happy when friends visited, able to say just a few words like yes and no to express his approval or disapproval of what transpired. [He] persevered in this state until April 23, 1921, when a massive stroke rendered him unconscious.” Hill passed away three days later on April 26, 1921, and a large funeral was held on the 28th. According to the report in Oregon Posten, “beautiful and expensive flower arrangements had arrived in great numbers: a harp from the children, a lyre from Luther College, an anchor from the Bethlehem Congregation, a broken wheel from the Carlsborg Congregation, and many other pretty flower symbols from the ministers of the district, the Carlsborg Congregation Luther Association, as well as from many different individuals.” Hill was buried at the Pioneer Lutheran Cemetery in Colton, Oregon, where his red granite headstone still stands with the inscription:

“Erected in fond remembrance of a pioneer teacher

of Luther College, Wahoo, Nebr. 1884 – 1915 Dr. S. M. Hill and

wife Julia by grateful pupils and friends.”